Evidence-based practice

at Midnight Health

Telehealth in Australia dates back to the 1920s, and the use of telegraph by the Flying Doctor Services. Nearly a century later, in 2013, the Australasian Telehealth Society urged wider adoption of telehealth in Australia. With the declaration by the WHO of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, the temporary payment of benefits for telehealth was enabled on the Medicare Benefits Schedule. This enabled the provision of telehealth care services by general practitioners, specialists, and allied healthcare professionals.(1)

The uptake of telehealth by Australians has been considerable, representing 17.2% of all consultations in 2022. By provider, in 2022, telehealth consultations represented: 21.9% of all GP consultations, 13.7% of specialist consultations, 27.1% of mental health consultations, 28.3% of nurse practitioner consultations and 14.5% of allied health consultations.(1)

In October 2020, The Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare was contracted by the then-Department of Health, to complete a review of the evidence for the effectiveness, safety and economic impacts of the provision of primary and allied healthcare via telehealth. The Institute completed the Review in February 2021. Since that Review, over two years of additional evidence on the effectiveness and safety of telehealth has been published.

The original report (Telehealth Review 2020-21) reached a number of conclusions about the effectiveness of telehealth which remain valid. Briefly, those conclusions were that telehealth – either by videoconferencing or teleconferencing – appears to provide equivalent clinical outcomes for many types of clinical encounter, particularly for ongoing clinical care.

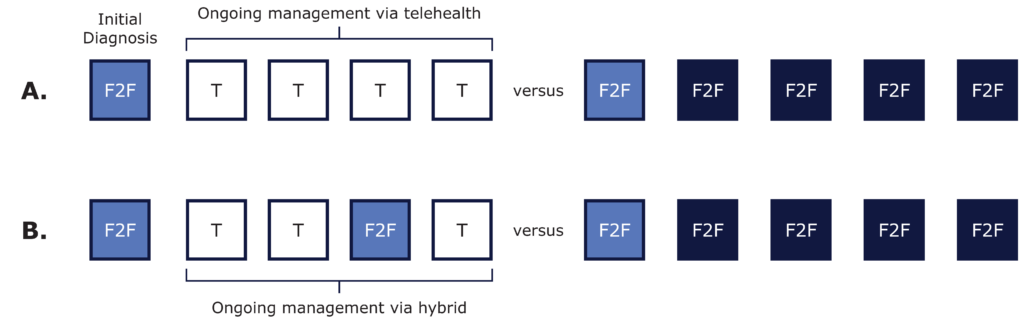

For continuing care for management of an established diagnoses (Figure 1 below), telehealth appears equivalent for most clinical outcomes, has similar cost to health services, increases convenience and access for patients, which is particularly important for rural patients and patients who have difficulty travelling to clinical appointments

Figure 1 Comparisons of telehealth (T) versus face-to-face (F2F) consultations. (A) An initial diagnosis followed by management via T or F2F, or (B) by hybrid.

Given the increase in convenience and accessibility, and decrease in cost for healthcare, video or phone consultations could be highly beneficial in primary care delivery (1).

Weight Management

The results show telephone and face-to-face consultations were equally effective for both short and long-term outcomes.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis via history of verbal assessment tool only – with no physical examination. For assessments limited to question-and-answer, such as cognitive assessments, telehealth appears equivalent to face-to-face.

While history taking and verbal assessments can be done acceptably by telehealth, only some elements of physical examination are sufficiently reliable and valid. Specific planning of physical assessments is often required, but this also suggests further research may overcome some of these limitations.

Mental Health – Depression

There is no difference between telehealth (by teleconferencing or videoconferencing) and face-to-face therapy for reducing the severity of depression and other key outcomes, in patients with depression.

Mental Health – Anxiety Disorders

We can continue to conclude that that CBT delivered by videoconferencing or teleconferencing appears as effective as face-to-face CBT in reducing clinically relevant symptoms for children and adults with anxiety conditions. This means that for treatment of anxiety disorders clinicians and consumers could choose communication modalities that are most appropriate for their clinical relationship.

Midnight.Health Patient Journey